Economic and social policies to date have focused excessively on fiscal discipline rather than on public investment in health and care, this crisis clearly showing that this was to the detriment of the people in general. This fiscal discipline focused on austerity, cuts and privatisation; as a result, aging was seen as a cost on the country’s budget and financing of the health sector dwindled. ETUC has been denouncing the weakness of the health care systems in Europe for many years.

ETUC strongly advocates that everyone, irrespective of age, is entitled to dignified living and health care. ETUC calls for a European approach that includes public investments, doubling the EU budget and issuing EU debt, in order to enhance EU forward-looking commitment for public and individual health.

Healthcare policy over the last decade and the approach towards the elderly

The European Economic Governance (EEG) repeatedly emphasised that, as the population is ageing fast, the costs of health needs of the elderly will soon be unsustainable for public budgets. Indeed, over the last decade healthcare was primarily linked to the cost of supporting an aging population and therefore a threat to fiscal sustainability.

Such an approach compelled governments to save on and cut public expenditure on health, in spite of the increase in care needs. A market-oriented approach on services that are supposed to be public because they are vital to the population, prevailed. This resulted, prior to the pandemic, that one out of three citizens was already renouncing treatments due to excessive costs.

The Covid19 crisis exposes how this short-sighted approach was detrimental not only (although outstandingly) to elderly people, but also to wide population groups and potentially for everyone in the EU irrespectively of their age.

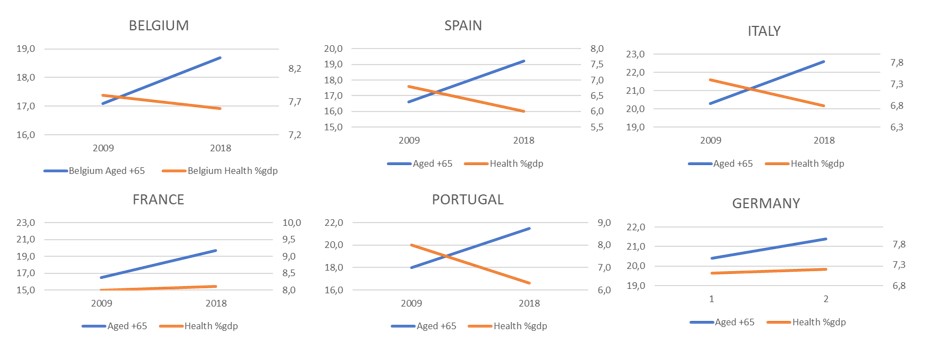

EPSU have repeatedly denounced the drastic reduction in public expenditure in health and long-term care as outrageous and anachronistic. Rather than investing in the sector, in particular when the ageing population increases and so its needs, the opposite has been done. The graphs below clearly show that while people are ageing, governments’ expenditure for health declines. There is widening gap between needs of the population and response of the state.

Figure 1 ETUC elaboration from Eurostat. Trends of population 65+ (left axis) and Health expenditure/GDP (right axis). The graph wants to visualise the increasing gaps between needs of population and governments' response in terms of expenditure

Reducing the investment in health care, when the population is supposed to need it the most, neglects the most basic of human rights, which is to “age in dignity”. The European Pillar of Social Rights takes a different approach. Health care is not considered a “cost”; rather a need and an opportunity for societal growth under several aspects.

The predicament of the elderly (especially in need of long-term care) was serious prior to the Covid crisis, now it is dramatic. In many countries, the lack of medical and public hospital supplies has led to the situation where carers have to select which patients to admit to intensive therapy on the basis of their life expectancy, which was done during war time. Some countries openly deny intensive hospital care for 80+ with other conditions in addition to Covid – giving them a death sentence.

Covid19 crisis exposes further inequalities

The socio-economic status of individuals determined their access to healthcare. Poor health is typically linked to a poor lifestyle, to inadequate working conditions and to arduous jobs. Women (trapped in low paid and “unattractive” sectors just like healthcare), elderly, migrants and atypical workers are the ones who, prior to the pandemic, already suffered from inequalities in access to appropriate healthcare.

|

According to Eurostat data on income inequality (2018), the difference in the income of the richest citizens (1/5 of the population) as compared to the poorest citizens (1/5 of the population) is as follows: in Germany 4.3 times greater, in France 4.6, in Great Britain 5.1 and in northern Europe less than 4 times as much. In Italy the income of the 1/5 richest citizens is 6.3 times greater than that of the 1/5 poorest. This places Italy is at the top of the ranking for the extent of inequality. In Europe on average the richest earn 5 times more than the poorest citizens. |

Evidence shows that the incidence of Covid19 deaths is higher among those with basic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes and heart or respiratory conditions. It is also empirically shown that poor living conditions, low salaries, low income and inadequate education impair a healthy lifestyle. By ignoring social inequalities, a vicious circle is reinforced whereby the more socially and economically disadvantaged a person is, the more his needs remain unmet, the more likely they are to suffer from health conditions, especially during a pandemic.

Self-employed workers, whose age is mainly between 30-50, can rarely afford access to insurance schemes and thus sickness benefits, and are forced to continue working even when it is risky for them or they are not healthy enough to work.

During a pandemic of the like of Covid19, inequalities are the magnified results of the economic governance perpetuating the reduction of public investment in healthcare, operating as cyclical with respect to income and wealth inequalities.

Healthcare workers under pressure

The relentless austerity approach hit hard on healthcare staff (over 70% of whom are female), who we are now praising and applauding every day. Also, such an approach has had consequent impact on the quality and the coverage of the essential services provided to patients.

Already incapable to meet the pre-crisis demands due to staff cuts, workers in the sector are under pressure even more during the pandemic, as excruciating work shifts and phycological pressure has increased. Across Europe, in addition to long-time frozen salary increases, poor compensations are now foreseen for extra-workload. Due to privatisation and marketisation of care services, many workers have no access to social protection and income maintenance measures that public employment would have granted. Furthermore, in some countries, COVID-19 infection contracted at the workplace cannot even be considered as an occupational disease and thus access to sickness and accident benefit is not allowed.

The health and safety of these workers is at risk, budgetary constraints have in many cases prevented the timely and sufficient provision of personal protection supplies – with negative consequences on the containment of the virus and fatalities among care workers, their families and patients (especially in long-term care homes in many countries). The serious impact of psycho-social and mental health of health workers as a consequence of the pandemic is completely unaddressed.

Healthcare and public funding emergency: keeping health costs low has cost human lives

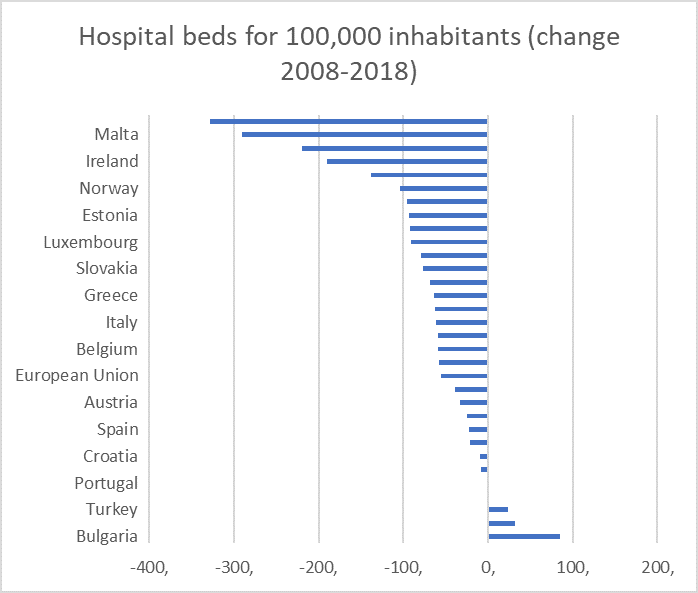

The Stability and Growth Pact has imposed cost cutting only on the basis of future projections of ageing statistics. However, the consequences are clearly measurable and are being paid by people already in the pre-crisis: the steady decline in GDP percentage and in real terms for healthcare across the EU; the increase in out-of-pocket expenditure by people to access healthcare; drop of number of hospital beds per inhabitant. With Covid, Europe’s capacity to respond to this emergency is severely challenged. The unpreparedness of care systems implies serious staff shortages uncapable to cope with the influx of patients; inadequate provision of personal protective equipment (PPE); lack of ventilators and testing capacity; sudden disruption of routine health services and medicine supply for people suffering from chronic conditions or under cancer treatment, as well as of the emergency services, ambulance services and general practitioners.

|

STATISTICAL NOTE: The government expenditure for the EU remained stable or declining as -0.1% of GDP in 2015 and 2017 (Eurostat). Public investments in infrastructures (that may include infrastructures for the health system or long-term care) declined. In 2008, personal money that people needed to cover health expenditure ranged between 12% and 28% of the total expenditure for healthcare goods and services. In 2018, this range varied between 10 and 45%. |

When, in September 2019 the ETUC opened the consultation with the European Commission ahead of the Semester cycle, it denounced that: “Access to health services and to long term care is an EU emergency. The past [decisions induced by the economic governance of the EU] promoted privatisation, “rationalisation” and “cost-efficiency”, usually implying aggregation of structures, shift of already allocated resources, de-hospitalisation of care, and almost never public investment in personnel and services that would be needed. Public spending needs urgently to progress in proportion to the most basic human needs and rights to dignified living conditions. ETUC supports collectively funded public health and care, including long term care services. Ageing populations should lead governments to spend more to protect elders and not less as the current SGP rules ask for… Investment in preventive healthcare, crucial in an ageing society, should be promoted and monitored.”

In reply, the European Commission called “inclusiveness (…) and continued or improved access to quality healthcare” as a core reform effort (Annual Growth Survey 2019).

In reply, the European Commission called “inclusiveness (…) and continued or improved access to quality healthcare” as a core reform effort (Annual Growth Survey 2019).

In reply, the European Commission called “inclusiveness (…) and continued or improved access to quality healthcare” as a core reform effort (Annual Growth Survey 2019). It was said that: “To ensure fiscal sustainability and maintain universal access to quality healthcare, Member States need to increase cost-effectiveness by investing in innovation, improving the integration of healthcare at the primary, specialised outpatient and hospital care levels and strengthening links with social care to meet the needs of an ageing population”.

An ambivalent, compromise wording, with no reference to investments in the sector to meet the needs, to the issues linked to the effectiveness of the privatisations, nor to long-term prevention.

The Commission was able to partly frame the challenge, also thanks to a consultation process that involves several stakeholders. However, the Council holds the responsibility of decisions as the ones taken for Country Specific Recommendations. In the light of these figure Member States’ responses were weak.

Eleven countries were given recommendations to reforms of health systems to increase fiscal sustainability and cost-efficiency (Finland, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia amongst other). Only a few countries received a recommendation for improving access to health services, including reduction of out-of-pocket payments and addressing shortages of health professionals (Bulgaria) or increasing investments in health system taking into account regional disparities and the need to ensure social inclusion (Greece and Portugal). For other countries, the Council had nothing to say on the necessity to reinforce health systems even if deeply analysed and requested at different levels. The CSRs did not even intervene according to the shortages of national systems as it was expected for Spain or Italy. It is not surprising that budgetary laws did not allocate resources for investments in this sector.

However, if the overall EEG imposes public budgets to comply with medium term fiscal objectives of containment of debt and deficit, there is no need of explicit recommendations to impact healthcare. The cuts to staff, wages and supplies in the sector respond to this fiscal priority, regardless quality care to all those in need.

The current economic governance is conceived in a way that cannot likely give a response to the investment needs of the EU economy. The economic governance did not incentivize investments neither in deficit countries nor in surplus countries; neither supporting public investments nor creating an environment for private ones.

Lessons from the crisis

Following the logic of “cost of ageing” we deprived an entire group of people of their future. A more forward-looking perspective to ensure quality healthcare imposes to spend more when the population is ageing, to better protect the elderly and not the reverse. Public spending needs urgently to progress in proportion to the most basic human needs and rights to dignified living across all ages and working conditions. So, the short as well as the long-term interventions at EU level should allow for the shift of governance rules and room for manoeuvre, enabling to address people’s needs at stake first – also for the sake of the economy, of the environment and of the European social model.

A shift of competences at EU level could be beneficial. The ETUC thus advocates an integrated European approach to public health, with clear EU competence to support national governments to work more closely together to tackle challenges and find effective solutions, and thus for supporting quality public services, increasing investments, doubling the EU budget, also issuing EU debt,

in order to ensure the multidimensional right-based approach of the SGD 3 and the EPSR principles 16 and 18.

We need an economic and social governance that invest and boost public and individual health protection and care in all MS:

- in multidimensional preventive policies, encompassing education, healthcare and occupational health and safety, in a life cycle approach;

- in the crucial health and long-term care sectors that can represent an opportunity to create more and high-quality jobs and thus drivers for overall societal return;

- in more qualified and skilled staff, as it stands they are already incapable to meet pre-crisis demands,

- in planning a strategy for qualifying efficiently and in a forward-looking perspective based on current and future care needs

- in addressing and tackling the socio-economic inequalities that affect access to healthcare;

- in strengthening the coordination between health care and social services; in developing socio-sanitary structures able to prevent and serve dependency situations

- in public funded research and development, to increase preparedness